“Be motivated. Don’t give up. Don’t quit on yourself. Take it day-by-day because each day is different from the next.” While those phrases of advice from Air Assault Instructor Staff Sgt. Aaron Patterson ring positively true and loud to anyone who has ever attempted or will attempt to earn the Air Assault Badge, he does add one caveat, “It’s only 10 days, but it’s the 10 hardest days in the Army.”

As Patterson leads Team I with officer-in-charge, 1st Lt. Allene “Ally” Somera, of nine other instructors from The Sabalauski Air Assault School (TSAAS) from Fort Campbell, Kentucky, the group is running five iterations of the 10-day school from June 22 through Aug. 6 at West Point with about 250 participants in each course.

Patterson is the Team I team senior while at Fort Campbell and is now the acting branch chief while the TSAAS instructor group is at West Point through the summer.

“It’s a big responsibility. I have filled that role (as branch chief) at the air assault school, but it’s much easier with other leaders around me,” Patterson said. “When I’m up here, it’s just me and my lieutenant, but it’s a good leadership experience. It’s slotted for a sergeant first class position, but I’m filling in as a staff sergeant … it’s above the realm that I’m used to, but I think it’s going pretty well, and it’s been exciting.”

As an air assault instructor, it’s about teaching the trainees what an air assault operation is about and the three phases of it.

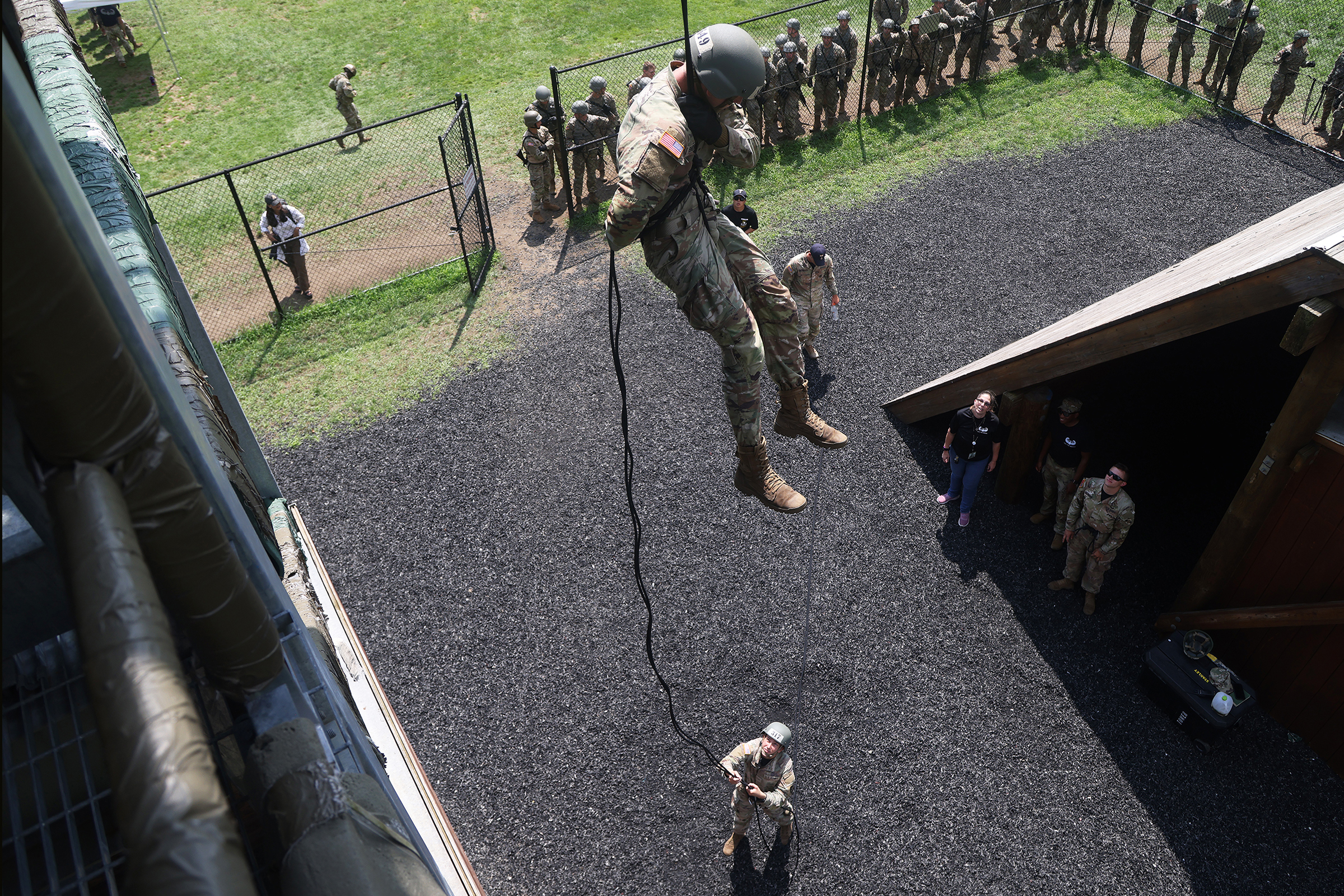

“We start with aircraft familiarization, then we move into sling loads. Sling loads are just moving pieces of equipment wherever they need to go through the air, over terrain, obstacles and on the battlefield,” said Patterson, who has been an air assault instructor since November 2020. “Then, rappelling operations, which is the movement of troops on the battlefield.”

The third iteration of the air assault school at West Point just completed on July 22 with the 12-mile foot march and the graduation ceremony of the class filled with U.S. Military Academy cadets, ROTC cadets, Summer Task Force Fury Soldiers from the 82nd Airborne Division who help train and oversee cadet cadre during Cadet Summer Training, and staff and faculty to include West Point Military Police and USMA second lieutenants waiting to go to their Basic Officer Leader Course.

The class began its session with 248 trainees, but after the equipment inspection, two-mile run and obstacle course on day zero, the iteration started with 227 participants on day one. But on the 10th and final day, 211 trainees stepped off for the foot march and all 211 rose to the challenge and completed the march under the three-hour time limit to earn the coveted Air Assault Badge.

The purpose of the course is to train Soldiers on the principles and techniques of air assault operations, sling-load operations and rappelling with each Soldier being able to perform the skills required to make maximum use of helicopter assets in training and in combat to support unit operations.

During the graduation ceremony, guest speaker Col. Nicholas Gist, the head of the USMA Department of Physical Education (DPE), recognized the USMA Department of Military Instruction (DMI) for its excellence in planning and executing the “world-class military leader development program;” the cadet cadre, 14 total through the two summer air assault details, for embracing their leadership detail; the air assault school cadre for bringing their expertise, experience and leadership to provide realistic training “essential to the readiness and lethality of our force;” and the graduates for their accountability and attention to detail to earn their badge.

“I ask that you do not leave here today and move on from the excellence you demonstrated, instead take those lessons learned and apply them in your daily work as you continue leading with positive professional habits like accountability and attention to detail,” Gist said. “You will now don the Air Assault Badge, which certifies you in contributing to lethal combat air assault operations. Moreover, the badge is an indicator of an individual commitment to the attributes this course instills … carry them forward with an inspirational commitment to standards and your relentless pursuit of excellence in all you do.”

To graduate from air assault school, one of the things that has led to failing out of the course is attention to detail. Patterson said that attention to detail is “the biggest killer right now.”

“Just focusing on minute and minor details that collectively help you finish … we harp on attention to detail so much, so when you get around to aircraft or boarding the aircraft or any piece of large equipment that you’re paying attention to the little details for safety, not getting anybody hurt and making sure that everything goes as smooth as possible,” said Patterson, a combat engineer from Smithville, Tennessee. “If you don’t pay attention to what everyone else is doing or what we’re telling you to do, you could very easily miss something. For example, this morning (July 21), we had to drop a Soldier before the ruck march because he didn’t put a phone number on his casualty feeder card.

“The casualty feeder card is a piece of paper that we give out and just in case you go down with a heat injury or a physical injury, we have somebody to contact if you end up going to the hospital or need further medical aid,” he added. “Those are high value safety items – ID card, ID tags and feeder card – and if you leave without any one of those three items before any physical event, you are not able to do that physical event.”

From Patterson’s perspective it is about securing equipment at all times, and it doesn’t matter if it is for a matter of safety or attention to detail, which means the trainees aren’t allowed to run or move anywhere with gear in their hands or allowed to move anywhere with gear in their hands.

“For safety and attention to detail, if you are around rotary-wing aircraft, you’re not going to be wanting to run around with gear in your hands or gear falling out of your ruck sack and straps flying everywhere – it’s the small things that could create a bigger issue,” Patterson said. “If we take care of the small things at the lowest level, the big issue won’t be an issue at all.”

Unfortunately, for this iteration as well as the second iteration, due to weather conditions, the trainees missed out on sling-load operations and rappelling from a UH-60 Black Hawk, which is provided by the New Jersey National Guard based in Lakehurst, New Jersey.

However, Patterson said that as the trainees hit phase 3 of their training, which involves rappelling, and working with the ropes on the ramp and the tower that there is no distinct difference between learning the ropes on the ground compared to rappelling from the rotary-wing aircraft, whether it is a Black Hawk or a CH-47 Chinook, which is used at Fort Campbell operations but not at West Point this summer.

“It’s the adrenaline, the experience more so than anything … you can do all that training on the tower as you can on the aircraft, and probably more,” Patterson said. “It’s the mental aspect, it’s the ‘oh, crap, I’m really here now, this is for real’ … if I don’t stay on my p’s and q’s, somebody can get seriously injured. If I’m not pulling blade control while my battle buddy is rappelling, he can end up getting injured.

“If I don’t rappel properly, I could end up smacking the bottom of the aircraft. Even us as instructors, we say this is the real thing, if I don’t make sure these people are hooked up properly on the rope, somebody could get seriously hurt,” Patterson added. “That is what we try to mitigate at all times and then just the adrenaline and giving those guys the experience because after Air Assault School, some of the cadets won’t ever be around an aircraft again, and that’s the unfortunate part of having to cancel aircraft operations due to the weather. But more so it’s the experience, it’s a great experience to rappel out of a bird from 45, 50, 60 feet.”

To make air assault School at West Point a well-oiled machine, it involves many parts working together in unison to make it all work. It begins with DMI, which was led by officer-in-charge, Capt. Scott Geary, who led the air assault summer detail to ensure everything required for the course was synchronized so everything could go as planned and as scheduled.

The first cadet cadre detail drew all the supplies, radios, vehicles, air assault handbooks, ropes and more to ensure when the air assault cadre arrived in June, that all the resources were available to them to conduct training.

Geary coordinated with the DMI land representative and range control for the Marne Confidence Course in the training area and the rappel tower on South Dock. He also coordinated with the New Jersey National Guard on the aircraft schedule, even though weather affected training on two occasions this summer.

Among the many people Geary recognized for their hard work and dedication for making this summer’s training go on without a hitch were Master Sgt. Jeremy Hinkle, Capt. Jillian Busby and, specifically, Julie Sommers.

“A critical member of the air assault team is Julie Sommers who has been at West Point for over 34 years,” Geary said. “She manages all slotting for the air assault course and is present during every critical event cheering on the air assault students. She works with the air assault cadre to complete drops in ATRRS and counsels cadets/drops on their ability to recycle into follow-on classes depending on their summer.”

But the personnel who make it happen on the ground is the air assault instructors and Patterson gives much credit to his guys on the ground whose due diligence helps more than a thousand trainees earn their Air Assault Badges.

“My team, they’re phenomenal. The majority of the team has been together a year at the garrison,” Patterson said. “They are great dudes to work with. They are super motivated, super smart because if I ever have to tell them something, I only have to tell them once. They’re good people first and it makes them good instructors. Team I is the best team at the Air Assault School at Fort Campbell – Team I leads the way.”

At Fort Campbell, there are three teams of instructors who teach throughout the year as Fort Campbell, which offers 40-plus classes yearly at its school.

As for Patterson, he is one of three instructors who returned this year from last year’s team that came to West Point. Last year, he was a primary instructor without a high responsibility position. This year, he has more responsibility in overseeing the training and making sure that everything they are doing is standardized through the course’s Plan of Instruction (POI).

“My first time, it was more so teaching the students, whereas this year it’s more teaching the instructors,” Patterson said. “This is my last air assault mission because I will be leaving Air Assault School soon after I return to garrison … this is my last chance to make an impact on the schoolhouse, the instructors and the students.”

Patterson will be moving on to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, to become a drill sergeant, so the love of teaching is definitely coursing through his veins.

“It’s going to be an experience for sure,” Patterson said. “I really enjoy teaching. That is what I’ve done for the last three years and that’s what I majored in while in college. It’s something I thoroughly enjoy, and I think it will be a great leadership development experience for me to better help the Army.”

Cadets earn their badges

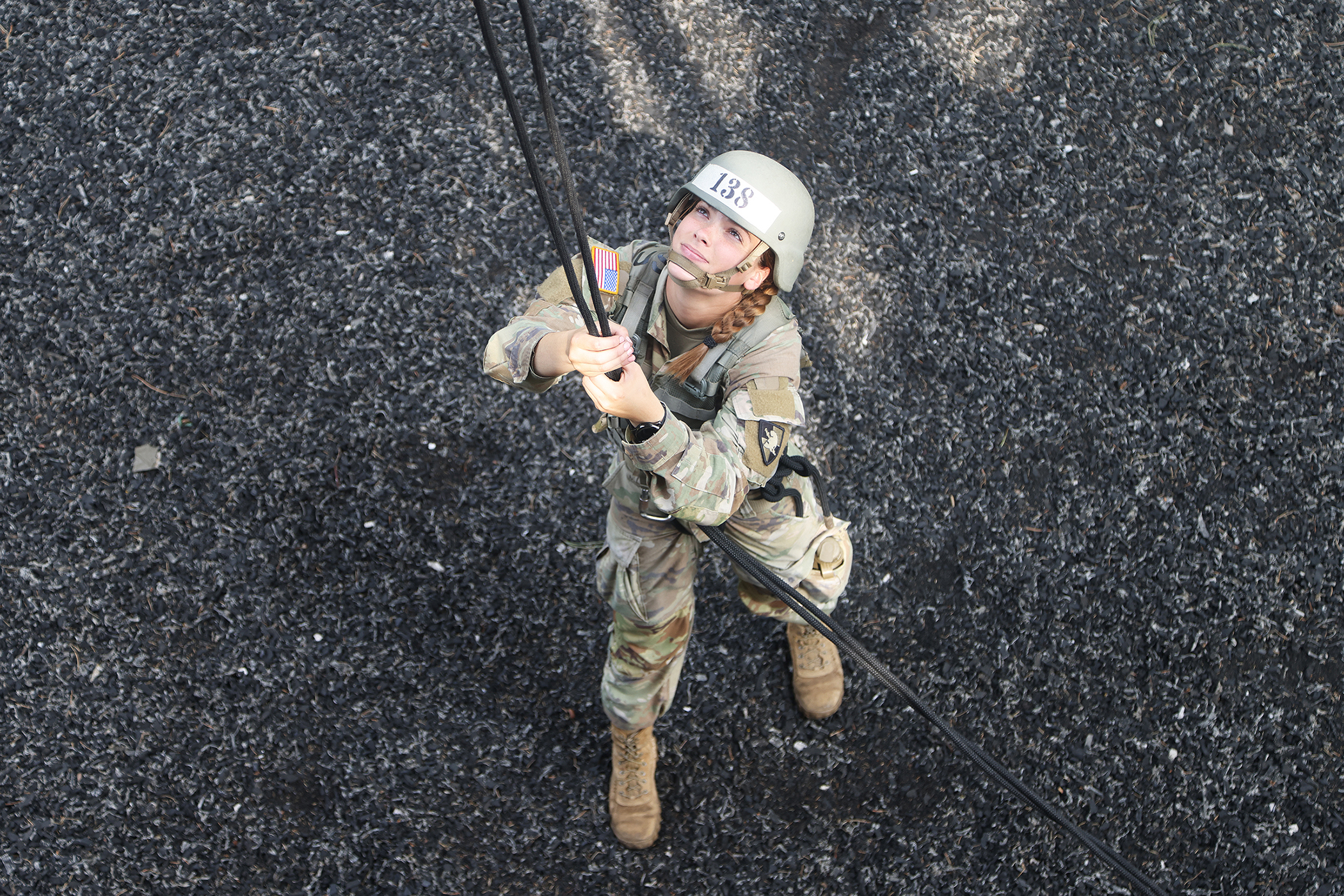

Going through the 47-month experience at West Point brings many ups and downs that it may feel like a roller coaster ride from academics to the physical aspect to the military training. No matter who you are – an officer, NCO or cadet – the air assault school is a daunting task to achieve earning its badge, and Class of 2025 Cadets Alana Kerner and Matthew Griffin earned their wings by satisfactorily completing the training course over the last two iterations.

Kerner, a Systems Engineering major from Ridgewood, New Jersey, thought it was great to take advantage of getting an air assault slot at West Point since she felt that “air assault slots are harder to get in the operational Army than they are here, so it’s a really good opportunity to take advantage of it as a cadet.”

From Kerner’s perspective, the training was extremely tedious both mentally and physically, although having it broken up into three phases helped make it seem shorter.

“Many of us had the shared experience of being very worked up for an upcoming task and believing that if we could just complete this one thing, we would be fine for the rest of the air assault,” Kerner said. “However, after completing that task, we felt the exact same way about the next one. After getting to the last thing, the 12-mile ruck, it was hard to believe there wasn’t still something left to do before we could get our wings.”

For Kerner, what made air assault school daunting started on day zero and the Marne Confidence Course on July 12.

“When I had gone through the Marne previously at Cadet Field Training (CFT), I wasn’t able to do some of the obstacles that are required at day zero (of air assault school),” Kerner said. “At CFT, there weren’t any consequences for that but at air assault failing more than one of the minor obstacles or either of the two major obstacles will get you dropped.

“Also, at air assault, you do a two-mile run in ACUs and a ton of other exercises before doing the obstacles, so you are already tired going into it,” she added. “I wanted to have the opportunity to go through the rest of air assault and getting dropped on day zero would mean I couldn’t do that, so I found that task to be very daunting and stressful.”

Stress does come with the notion of being exceptionally sharpened on attention to detail, a part of the course that tends to drop trainees more so than any physical aspect of the course, and that was no different for Kerner during her class.

“I found myself, along with almost all of my peers, being excessively careful and obsessive about the small details,” said Kerner, who hopes to branch Field Artillery in the Army. “With regard to the layouts, no matter how many phases you have completed, if you forget an item on the packing list, you have to restart air assault from day zero. With that in mind, we found ourselves checking the packing list over and over.

“We would close our rucks and tighten them up so not to be worried that something inside grew legs and walked away,” she added. “Then, we open them back up again to make sure it’s all there. Keeping track of all of the items required a higher level of organization than what I personally am used to and that is a skill I can take with me through my time as an officer.”

One unfortunate aspect for Kerner’s iteration was not being able to perform aircraft operations due to the weather as she was looking forward to rappelling out of the helicopter.

“That was a big reason why Day Zero was so daunting – I knew if I didn’t complete it, I wouldn’t get to do that,” Kerner said. “It’s definitely disappointing to miss that part of the training as I may not get a chance again and it would have been a really cool way to wrap up the detail. On the other hand, because we didn’t go out of the helicopters, we had almost the entire day off before the ruck, so it was a win either way.”

Kerner was extremely excited about earning her Air Assault Badge when you add all the flutter kicks, Y-squats and low crawling the group had to do during the iteration.

“It’s a really good feeling to look back on the past two weeks and remember all the hard work I put in knowing how much easier it would’ve been to not stick through with it or not attempt it at all,” Kerner said. “Now, I get to see all the hard work in the badge.”

Looking at the badge will also be a reminder to the Task Force’s namesake, Task Force McMahon. West Point summer details are named after graduates who died while serving in combat. The air assault detail throughout its five iterations is named after Lt. Col. Michael McMahon, a 1985 USMA graduate who died in a plane crash serving during Operation Enduring Freedom in 2004 in Bamiyan, Afghanistan.

The detail includes McMahon’s son, Class of 2025 Cadet Dennis “Ricky” McMahon, who served as the S-4 during the training.

“Being such close friends with Ricky McMahon made it really special to complete air assault under this namesake with Ricky there at the detail, too,” Kerner said.

Overall, Kerner looked at doing air assault school as a “rewarding experience,” and would have a discussion with anyone who thinks achieving the badge is not hard.

“Air assault is hard and it’s an accomplishment to complete it,” Kerner said. “It’s an accomplishment to show up and attempt it. I’m proud of myself, my friends that I knew before air assault, and my friends that I made at air assault for getting through this.”

Griffin knows exactly what Kerner means by “getting through this” as he graduated the course during the previous iteration. However, his journey wasn’t just the 10 days from July 5-15 that his iteration went through air assault school.

For Griffin, a Defense and Strategic Studies-German double major from Weston, Connecticut, he was dropped from the course last year on his first attempt, but life is full of second chances and his second chance this year came with a pair of wings to display on his chest as a result.

“It was important to me to overcome the challenge and earn the badge this year to prove to myself that I was up to the task,” Griffin said. “I was in air assault 5 last summer and due to that, I did not have the chance to recycle into phase 2 again, which was where I was dropped from the course previously.

“Command Sgt. Maj. (Robert) Craven spoke at my graduation and recalled his experiences as a young Soldier getting dropped from the course and going back to eventually pass,” he added about the U.S. Corps of Cadets command sergeant major. “I was grateful to have been given a chance to come back this year and earn the Air Assault Badge.”

Last year, Griffin was dropped after the hands-on examination part of the A-22 Cargo Bag inspection. He only identified two out of the four deficiencies in how the A-22 Cargo Bag was rigged for use in a sling-load operation.

“My two minutes expired, and Air Assault Instructor Staff Sgt. (Calvin) Collins turned to me and said, ‘At this time, air assault, you are a no-go.’ I also failed to pass the retest a few hours later and was subsequently dropped from the course,” Griffin said. “This year, I concentrated on staying calm, collected and focused on the task at hand when the test began. This was possible because I took advantage of the time we were given to practice on the properly rigged sling loads.

“Also, the class put in extra practice at the ‘late man’ session the night before the test after hours at South Dock,” he added. “Due to this I felt prepared and when it was time to perform, I was ready. I was able to successfully identify four out of the four deficiencies on the A-22 Cargo Bag this year and came in safely under the time limit.”

In failure, sometimes great lessons are learned about yourself, and Griffin did see the value in failing and coming back strong.

“The greatest lesson learned that will help me in the future as an officer is that leaning on teammates allows you to recover from failure quicker and come back even stronger,” Griffin said. “Going through the course a second time, I helped others to prepare, which in turn, helped me with all aspects of the course … I was looking to my left and right to encourage others and for the encouragement that arises in shared hardship. Working with others to help them avoid pitfalls that stopped me on my first attempt served to elevate their success as well as reinforce my confidence in what I was doing during the course.”

Griffin had a chance to see a few familiar faces since three of the instructors returned – Patterson, Collins and Staff Sgt. (Ryan) Cheesman – and said they upheld the “same level of standards, passionate instruction and professionalism this year as they did last year.”

Griffin believes that becoming air assault qualified does “demonstrate proficiency in important aspects of officership and skills that are tested.”

“Attention to detail, resiliency and performance under pressure are just a few of the skills that air assault teaches beyond the primary qualification to inspect sling loads and use helicopter assets in training and combat,” said Griffin who hopes to branch Field Artillery in the Army. “These are all applicable to any branch of the Army and any officer benefits from possessing these skills in leading Soldiers.”

Griffin found the rappel phase as the most interesting and exciting part of the course as it was the first time he ever rappelled and learned how to tie a Swiss seat. However, his iteration had weather issues as well to where his group didn’t get a chance to rappel from the Black Hawk at the end of phase 3.

“It was disappointing to miss out on rappelling out of a Black Hawk and to see what a sling-load operation can look like outside of a classroom environment,” Griffin said. “However, we still were able to experience free rappelling out of the rappel tower, which is something I had never done before, so that made up for it a little bit. The day we were going to rappel was the day in which the flooding and damage occurred at West Point, so all of the students in the class understood pretty clearly why the helicopters could not takeoff that day.”

Air assault school is training that hits hard from both the physical and mental perspectives, and Griffin mentioned that at the same time you have to be careful and attentive with everything you do in the course and he would give that advice to anyone who tackles the school in the future.

“Show up to the course physically and mentally prepared for the challenge of the 10 days,” Griffin said. “Prepare to exert significant effort on studying and preparing for the exams that are part of the course. Proper mental preparation should include the work ethic necessary to study the content and the essential attention to detail that is needed for the whole course.”

In the end, Griffin said the experience was meaningful to him to finally receive the Air Assault Badge that eluded him the previous year.

“I was so excited after passing the 12-mile ruck march and the final gear layout to graduate,” Griffin said. “My sponsor and mentor, Maj. David Frye, was there to pin my wings on me at graduation, which is awesome as he encouraged me to go through the school a second time to ‘get my wings.’ It was especially rewarding to graduate with some cadets from our iteration last summer who didn’t have the opportunity to recycle and finish the school. I also completed the school with my first semester plebe, Alex Christensen, which was exciting to see him succeed in the course after he crushed Cadet Field Training a few weeks prior, where he earned the Recondo Award.”

(Editor’s note: Part II of the air assault feature will focus on the name of the air assault task force, Task Force McMahon, and the meaning behind it.)